TLDR version: Theodicy is the question of why evil exists when God is supposed to be good. There are lots of approaches to this question, I’ll be pursuing one of them in the next article.

Over the next few weeks I plan to publish a number of blogs looking at some important questions of Christian theology, and giving what might for some be a new perspective on them.

I’m always keen to acknowledge that my own perspective is forever evolving, I know I’m wrong about some things, and I’m in a constant process of learning. I think of this as a ‘grounded mind’ approach: its an acceptance of our flawed humanity, and that we’re not in a position to know or understand everything. My opinion is that this is the most healthy approach any of us can take, in fact I distrust any other approach.

Certainty is too much of an idol for most of us. Doubt and faith make much better bedfellows than certainty and faith, a combination of the first sort produces humility, the latter tends to produce arrogance. Tweet this!

On that basis, I hope some of these thoughts develop into conversations, genuine discussions of perspectives on truth. But for that to happen we need to share some conceptual language. One of the most important concepts in theology, is that of ‘Theodicy’ – so what does that mean?

The word theodicy is not particularly old, only a few centuries, it was developed by a theologian looking at one of the most fundamental issues for any one who accepts the idea of ‘God’ – whatever form that may take. The question is: ‘How can a morally good God exist in a world which is so clearly full of bad things?’

Since it’s coining, theodicy has been explored by various theorists and writers, not all of them theologians. For instance, Max Weber, the sociologist, considered theodicy to be a human response to a world in which many things are difficult to explain. Perhaps the most common reframing of this kind of concept, is ‘why do bad things happen to good people?’ (Personally I prefer to ask the opposite question.)

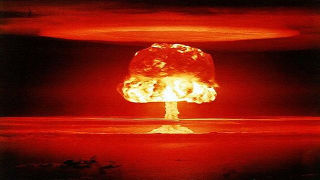

But in a theological sense, theodicy concerns the question of why a/the God would ‘allow’ or ‘permit’ suffering. What is the meaning of evil in the face of an ultimate goodness? It does require a starting point of an acceptance of God as in some way objectively ‘real’ – although precisely what that means remains debatable.

Various answers have been formulated to address this question, they include ideas about the purposes of evil, and the nature of God’s will. All of these arguments have strengths and weaknesses, which are well addressed in relevant pieces of literature. In the next few posts I will ask some of the fundamental questions about the nature of God which help us get to the root of this problem – in particular I will ask if God should really be understood as ‘all powerful’ and ‘in control’, and also whether God can be said to be ‘unchanging’.