Thomas Jay Oord is a serious philosophical theologian with a common touch. He’s able to articulate complicated ideas and subtle concepts in simple language which scratch where the average reader itches.

God Can’t, published in 2019, proved to be popular with readers precisely because it put into accessible terms the kind of ideas that Oord has been expounding for some time, namely that God does not sit idly by while the planet burns and humans kill one another refusing to act except by occasional whim. Rather than refusing to act “God can’t”, Oord insists.

God Can’t, and its now companion piece God Can’t, Q&A (published in 2020) are aimed at readers who want to reconcile their conviction that somehow God is “real” with a growing body of experience that says things aren’t the way they should be. Tellingly Oord foregrounds the experience of real people, using small case studies in the former, and reflecting on readers’ questions in the follow up. He does this to great effect, and does his very best to avoid the usual dodges employed by confessional theologians – taking aim particularly at the “it’s a mystery” trope favoured by those who struggle to articulate or justify why a good God might allow or even ‘ordain’ suffering.

In 2015 Stephen Fry launched in to a blistering televised critique of the interventionist God who chooses not to intervene. The video went viral, Fry had articulated the basic problem with so much of popular Christian thinking – effectively that the God who allows unspeakable torment of blameless creatures is some sort of monster.

What Oord exposes is that there is an alternative view of God which takes seriously this critique and offers a plausible alternative. Along the way he also points out other problems with the idea of an omnipotent deity. “Its hard to feel motivated to solve problems an allegedly omnipotent God could solve alone…” he muses, putting his finger on the reason why so many Christians smile blithely in the face of climate catastrophe and political despotism.

At times the writing is almost preacherly, reflecting the pastoral vocation that competes for time with Oord’s academic work. Indeed it is perhaps this vocation which has caused problems for Oord in the past, he has previously fallen foul of institutional powers that be which objected (unjustly) to his deeply pastoral theology. He falls foul too of those who think that he is saying that God is entirely powerless – but that’s a shallow reading of his thought. God, according to Oord, is still ‘al-mighty’ but needs our cooperation in order to effect change. Love never coerces, he argues. Here he is squarely in the realm of neo Whiteheadian Process theology as he begins to talk about ‘indispensable love synergy’ and even refers sparingly to the ‘lure’ of God among other less technical metaphors. Perhaps this area exposes one of the potential weaknesses in his theology (shared by some other process theologians) the insistence that at times even individual cells in the body might respond to God’s loving lure. This kind of explanation is given here and in other similar literature to explain some ‘healing miracles’ and other unexplained answers to prayer. Personally I find this panpsychist explanation not to be entirely convincing, and worry that it verges too closely to the ‘mystery’ argument which Oord does so well to dispense with.

Confessing Christians, particularly those who take a ‘high’ approach to the Bible, will appreciate his approach. Those who take a more literary approach to Biblical texts might find his reading of certain passages a little over worked. This does however make him an excellent interlocutor for evangelicals looking for a better way to understand the God of their upbringing, and crucially it doesn’t spoil the great thinking or writing.

In “Q&A” Oord tackles some of the obvious questions which arise from his first – If God can’t, then ‘why pray?’ for instance, and questions about the afterlife among a variety of others. Here again some readers will struggle with his adherence to what I would term ‘Biblicism’ (his apparently literal approach to the virgin birth for example) but he remains entirely coherent in his argument, and sticks closely to his brand of Christianity without ever making exclusive claims to truth. Perhaps at times the conversational tone he employs, which makes the books so readable, isn’t quite adequate to the task of unpacking complex ideas, the nature of God for instance would perhaps be better tackled in more technical language. This might have assuaged some of his critics, but it would also have defeated the point of the exercise.

Throughout the books he advances an idea of God which is panentheist and kenotic, but he does this in a personal and personable way which manages not to alienate or confuse the average reader. His tight prose keeps the reader moving through the books and his consistent recourse to ‘every-man’ stories from his friends and readers means the whole thing remains firmly rooted in the day to day realities of life.

I would have liked him to reject some of the problematic approaches to the Bible which lead many to adopt the erroneous view of God which he spends so much of the book addressing, but perhaps it’s more powerful for his not doing so. Again his pastoral heart is evident as he takes the beliefs and concerns of the reader seriously, and addresses them from a place of love and respect.

The Christmas stories in the Bible have a message – and it is neither the commodified story of contemporary culture, nor is is the cutesy baby in a stable nativity scene. It’s a story of political subversion and social reversal, set in a particular time and place.

The Christmas stories in the Bible have a message – and it is neither the commodified story of contemporary culture, nor is is the cutesy baby in a stable nativity scene. It’s a story of political subversion and social reversal, set in a particular time and place. There’s a story in the Hebrew scriptures, about the people of Israel after they had escaped from Egypt. In the story, which is absurdly rich in symbolism and image, the people are making their way through the desert when their leader Moses climbs a mountain to commune with God.

There’s a story in the Hebrew scriptures, about the people of Israel after they had escaped from Egypt. In the story, which is absurdly rich in symbolism and image, the people are making their way through the desert when their leader Moses climbs a mountain to commune with God. There comes a point in most people’s lives, when things have to be taken apart. Beliefs, world views, ways of understanding yourself, and what life is all about.

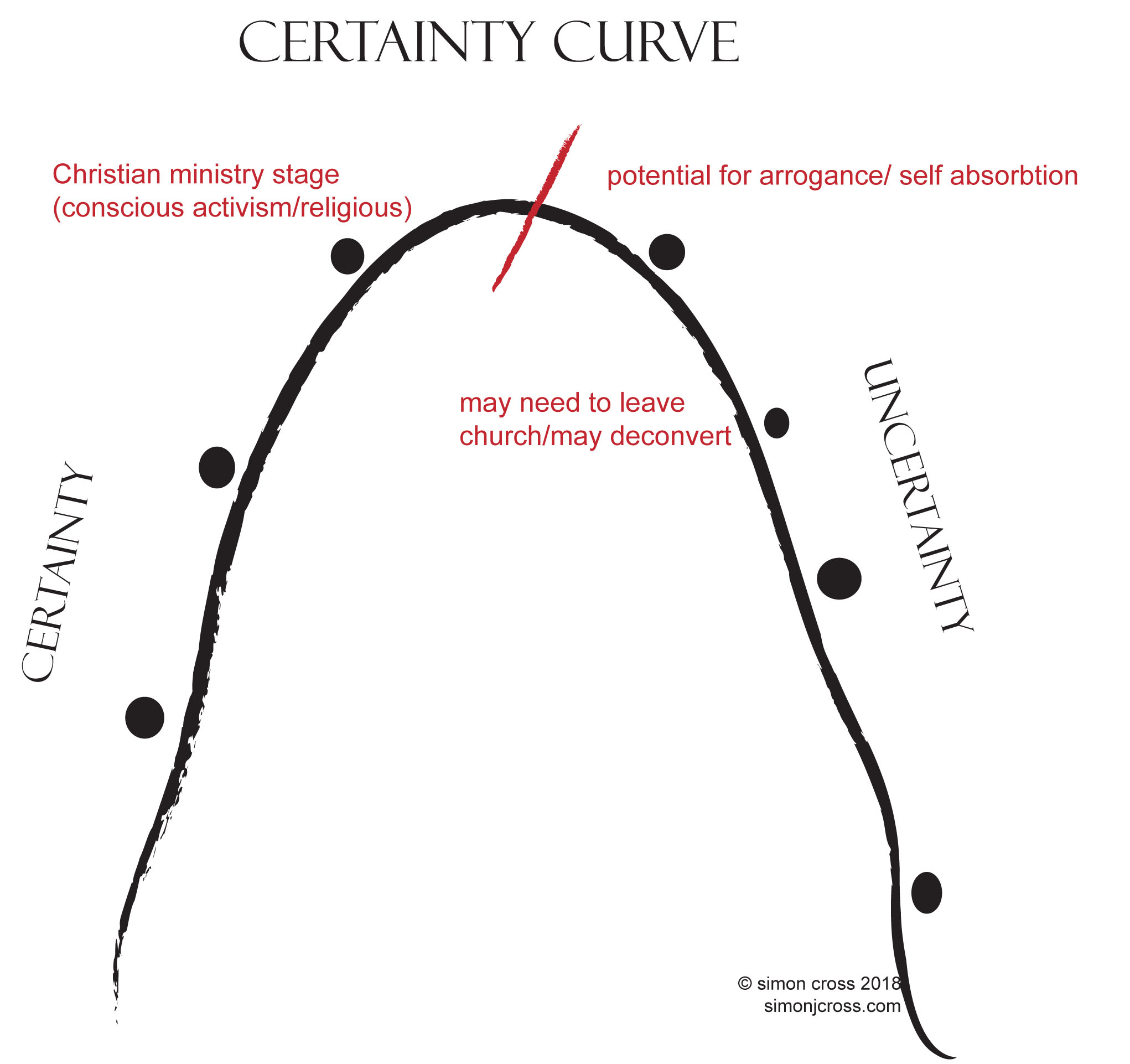

There comes a point in most people’s lives, when things have to be taken apart. Beliefs, world views, ways of understanding yourself, and what life is all about. My post about

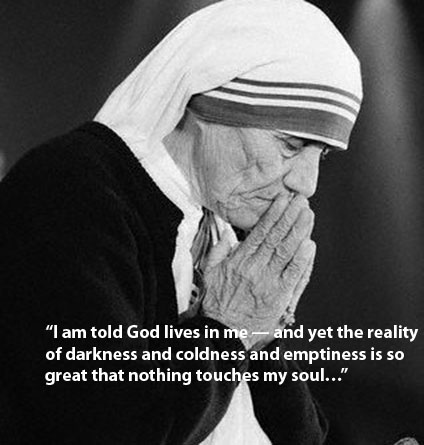

My post about  So in the story, the son leaves home, and becomes physically distant from his father – in a similar way someone may leave the certainty of evangelicalism, or any other dogmatic view of God, and become physically distant from the church. This is the beginning of his period of deconstruction, during which the proto evang-exiter may become arrogant or conceited about his or her journey. ‘I know the way to live, and it’s nothing like the old way…’

So in the story, the son leaves home, and becomes physically distant from his father – in a similar way someone may leave the certainty of evangelicalism, or any other dogmatic view of God, and become physically distant from the church. This is the beginning of his period of deconstruction, during which the proto evang-exiter may become arrogant or conceited about his or her journey. ‘I know the way to live, and it’s nothing like the old way…’ Another example is the disciple Peter (a non evangelical of course), who goes through a similar process to the Prodigal son. In this case, Jesus is the God-figure, the point of ultimate concern. In the first place Peter is dependent upon Jesus, seeing Jesus as the answer to everything. Jesus is all powerful at this stage in their relationship, and Jesus is at his miracle performing best. As things develop, Jesus plays an almost parental role in Peter’s life – he has left his family to follow him. But then crisis hits, and all of a sudden the miracle working Jesus has gone, and a new captive, powerless Jesus has emerged. This throws Peter in to a state of turmoil, and he finds himself denying the master he had followed so closely until now. At the point of Jesus’ death, Peter is at his most distant, entirely removed from Jesus. He is not arrogant at this point, rather he is broken, which demonstrates that everyone walks this path in a unique way. Peter’s re-encounter with Jesus is his experience of the mystery of un-earned grace, and he moves into a place of all pervasive love and acceptance. Does this make him perfect? No. Does it make him totally wise and enlightened? Again no. This illustrates that this is not a simple process as this curve would make it appear, this is not the end of Peter’s story. He goes through a new set of curves, crises, and moves forward. But this curve is quite clear, he tips over the edge of certainty.

Another example is the disciple Peter (a non evangelical of course), who goes through a similar process to the Prodigal son. In this case, Jesus is the God-figure, the point of ultimate concern. In the first place Peter is dependent upon Jesus, seeing Jesus as the answer to everything. Jesus is all powerful at this stage in their relationship, and Jesus is at his miracle performing best. As things develop, Jesus plays an almost parental role in Peter’s life – he has left his family to follow him. But then crisis hits, and all of a sudden the miracle working Jesus has gone, and a new captive, powerless Jesus has emerged. This throws Peter in to a state of turmoil, and he finds himself denying the master he had followed so closely until now. At the point of Jesus’ death, Peter is at his most distant, entirely removed from Jesus. He is not arrogant at this point, rather he is broken, which demonstrates that everyone walks this path in a unique way. Peter’s re-encounter with Jesus is his experience of the mystery of un-earned grace, and he moves into a place of all pervasive love and acceptance. Does this make him perfect? No. Does it make him totally wise and enlightened? Again no. This illustrates that this is not a simple process as this curve would make it appear, this is not the end of Peter’s story. He goes through a new set of curves, crises, and moves forward. But this curve is quite clear, he tips over the edge of certainty.

I’ve realised from the responses I got from

I’ve realised from the responses I got from  Surviving the death of the tradition that raised you.

Surviving the death of the tradition that raised you.